Committed to Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements for All

In Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC

Abstract: The author of this article points out that most cities lack green planning for sustainable development. Rampant urban sprawl has caused a series of environmental, social and economic consequences, posing challenges for urban planning. Therefore, the author proposes to adopt the strategy of smart growth and traditional neighborhood development (TND), and at the same time puts forward the ideas of integrating International Green Model City (IGMC) Standards with SmartCode and TND in accordance with specific context. By doing so, IGMC is expected to create best development practices of green and sustainable city which is characterized by complete, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods, newest environmental protection technology, and effective green transport and infrastructure. And IGMC can become a paragon of scientific planning.

A Planning Paradigm in Green Urbanization

Much of the discussion in

Asia on the greening of its cities has taken its cue from the western

hemisphere, focusing on the more popular low-carbon strategies, such as

employing energy efficient fixtures and appliances; generating and using clean

energy such as that from the sun or from wind; recycling and using recycled materials;

incorporating green roofs and walls; and even incentivizing if not requiring

the use of fuel-efficient vehicles (e.g. hybrid cars).

While these, often

technology-oriented, approaches all contribute to mitigating the environmental

impacts of urbanization, very little attention has been paid to addressing the

patterns of development and the sustainability (or lack thereof) of these

current patterns.That is, there appears to be a gap in the green policy when it

comes to a suitable physical planning oriented response.

The Problems

of Sprawl

China’s rapid growth has given rise to urban sprawl. Cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou have increasingly notorious reputations for their ever-expanding urban boundaries, choked traffic and heavy pollution; new developments also follow a similar pattern, driven by road projects into rural areas and taking up precious agricultural land.2

As

has been experienced in the United States, sprawl promotes the segregation of

land into pods of single use, creating car-/vehicle-dependent developments with

enormous land footprints. Among the numerous consequences of such a pattern of

urbanization include:

• disproportionate land consumption, conversion of agricultural land and degradation of wilderness and habitat;

• over-provided road infrastructure, long commutes, traffic and increased road fatalities;

• severe pollution levels and diminished quality of life and health; and

• economic

losses and diminished social capital.

Clearly,

sprawl presents severe impacts not just to the physical environment, but to

other areas of development as well. Indeed, the last three years have seen the

unprecedented confluence of several international development crises: the

mortgage meltdown and the diminishing returns of suburbia; peak oil, rising

fuel costs and unsustainability of driving; climate change and the need for

green/environmentally responsible development; the migration to urban cores by

both aging Baby Boomers and Millennials; and the growing need for food security,

as well as for physical security and safety. The one thing these issues have in

common is the promotion and export of the lifestyle of the (American) middle

class, which is founded on sprawl and which is arguably at the heart of all the

major problems associated with development and growth across the United States

and overseas.

Andres

Duany, in an article for Newsweek (October December 2003), wrote,

“The great cities of Asia are hailed as the metropolises of the new millennium. Indeed, their scale and pace of building is breathtaking… Today’s Asian architects and city planners have ambitions…so astonishing that one could easily overlook a possibility that they are adopting an outdated model of urban development, one that’s already been discredited by the experience of the West... Asia is building, but not the great cities of tomorrow.” 3

The Convenient Solution

At

this juncture, it is imperative that China avoids what has been proven to be

clearly a detrimental mode of urbanization and instead adopts a more

sustainable approach to development. Smart Growth and Traditional Neighborhood

Development (TND) offer the most viable solution for accommodating new growth

in a changing environment, under an approach that is more fundamental than

continued investment in development frameworks and infrastructure programs that

perpetuate sprawl. They offer the convenient solution to a cadre of

“inconvenient truths”.

At the

regional level Smart Growth/TND promotes environmental conservation;

development footprints are much more compact, allowing the preservation of open

space and agricultural lands, as well as facilitating better stormwater

management. Green neighborhoods are planned with equitable distribution of

public transportation and housing, so that important destinations such as

employment, cultural and recreational centers are served by public transit,

reducing car dependency for most daily needs. At the neighborhood level this

planning strategy promotes rationally organized, mixed-use, mixed-income,

pedestrian-friendly increments of community building.4 The following

are specific comments offered in response to the IGMC Standards Draft vis-à-vis

Smart Growth and Traditional Neighborhood Development, for the consideration of

the GFHS.

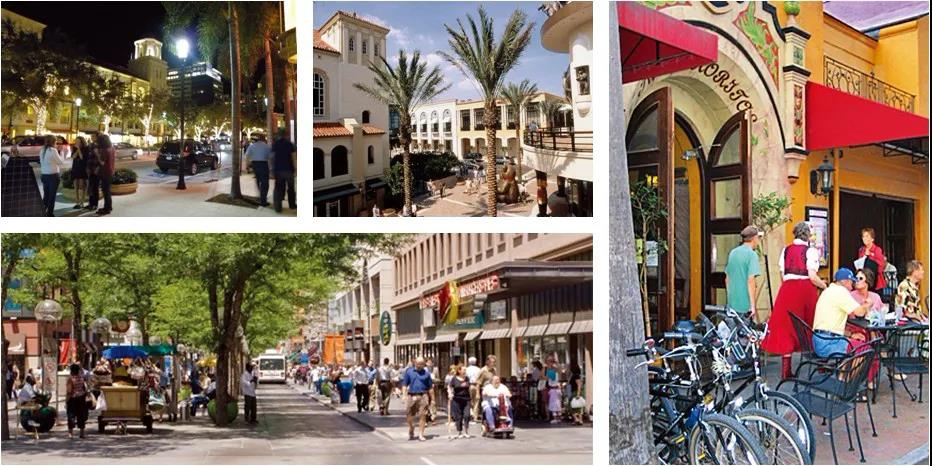

Livable community model

The IGMC as a

Multisectoral City

The

IGMC is currently proposed to be developed with six “themed” Blocks, one each

for Conference/Training, Head Office, Business, Resort, Residential and Support

uses. If this new city is to be truly green, its development should begin with

its planning and design in traditional neighborhood increments5 with

mixed uses, compact development footprints and connected street networks. As it

happens, at 337 hectares, the proposed new city will in fact comprise some six

neighborhoods; while the proposed primary uses may be generally retained, it is

crucial that each neighborhood have some degree of mixed use as opposed to

segregated zones as currently suggested by the themed Blocks.

Traditional

neighborhoods allow multiple market segments to exist in close proximity at 1/3

to 1/2 the land footprint and 1/3 to 1/2 the infrastructure cost. Moreover,

cities made of neighborhoods are better for balancing resource needs and

distribution; with each neighborhood being a complete community, there is less

competition for increasingly scarce resources. More land is retained for open

space and agriculture, and driving for daily needs is significantly reduced.

The IGMC and Green Transportation

Green

transportation within the IGMC can be made more effective when the community is

organized/structured in neighborhood increments (i.e. Transit Oriented

Developments, or TODs). With six walkable neighborhoods, each with a transit

stopat its center, everyone is within a 5-10 minute walk to transit, and the

fewer (only six), but more rationally located, stops maximizes transit

efficiency.

Density

is logically intensified around transit, optimizing land use with more compact

development footprints. Having the stops located at neighborhood centers (e.g.

with a café, newsstand or other community/civic facility serving commuters)

also incentivizes transit use by making it a pleasant experience. Last but not

least, planning and design using the neighborhood increment encourages, and

allows the seamless integration of, other alternative modes of circulation,

including biking and walking.

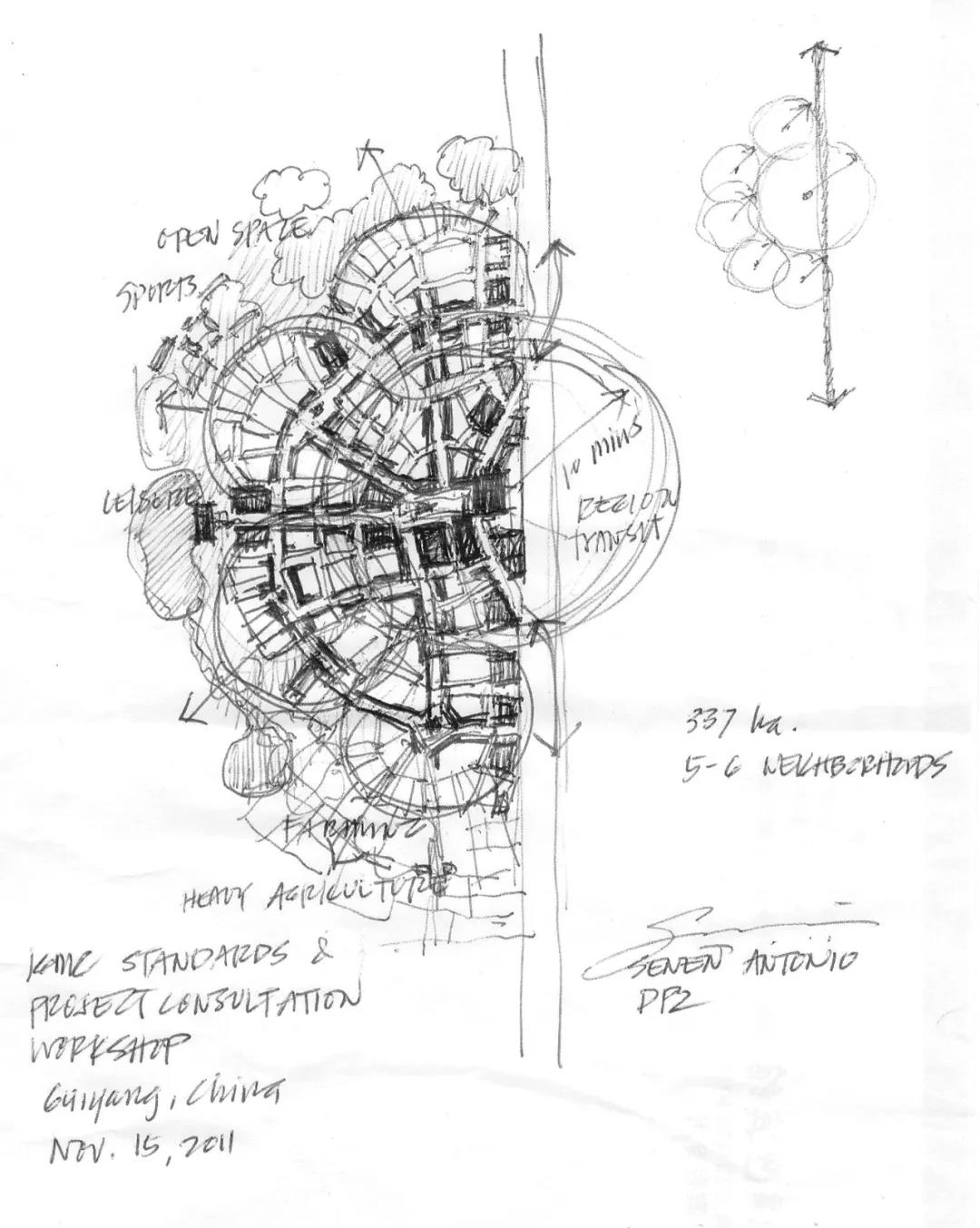

The hand drawn sketch plan of IGMC Guiyang project by Mr. Senen during the IGMC Standards Workshop

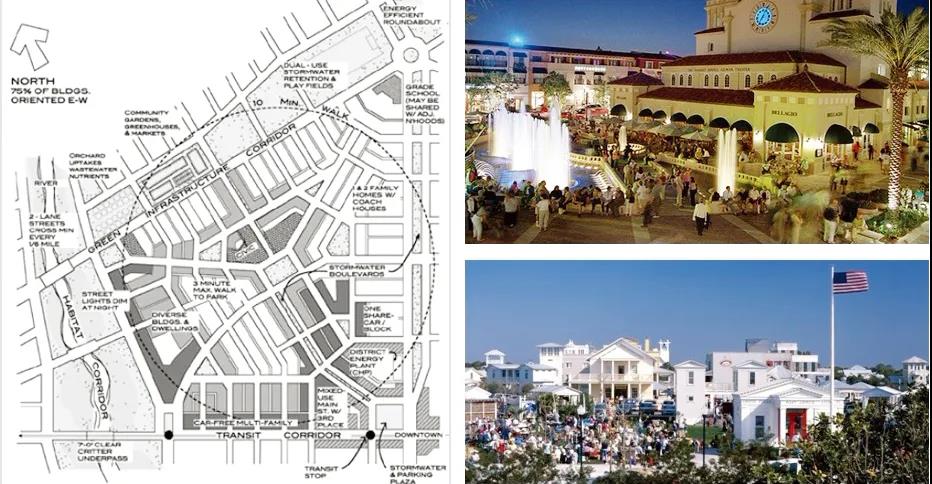

The IGMC and Green Infrastructure

The IGMC Draft Standards anticipate that green infrastructure will cost 6 to 8% more than conventional engineering. However, with traditional neighborhood infrastructure (e.g. Green Streets or Light Imprint urbanism), the costs can in fact be 10-15% less.6

Light Imprint (LI) is a

comprehensive development approach for the sensitive placement of development

via coordinated sustainable engineering practices and traditional neighborhood

design techniques, balancing environmental considerations with design

objectives such as connectivity and a well-defined public realm. Light Imprint

provides, for example, a toolkit for storm water management using natural

drainage, traditional engineering infrastructure and filtration practices,

employed collectively at the scales of the sector, the neighborhood and the

block. In using context-sensitive design solutions (i.e. not “gold-plating” the

engineering throughout the development), Green Streets and Light Imprint are

able to significantly lower construction and engineering costs, while

generating a range of environmental benefits combined with an aesthetic

approach to infrastructure.7

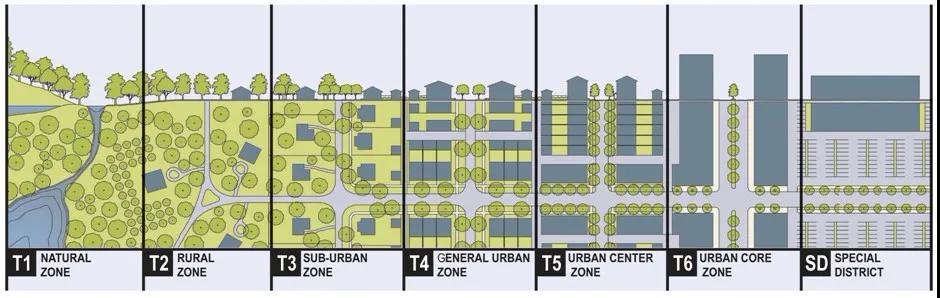

The IGMC Standards Draft

emphasizes the need for an effective framework for implementation; in TND

planning, the New Urbanist Transect, adopted from the natural transect used by

ecologists and calibrated to the best practices within the local traditional

development context, is an effective scientific tool for classifying and framing

the continuum of traditional urban development patterns.

TND planning requires the

replacement of the single-use zoning regulations with form-based zoning and

coding. Form-based coding employs the Transect as the scientific basis for

regulating urbanism, allowing greater predictability in the public realm

through regulations and standards that primarily concern physical form,

character and relative density and mix of uses.

Per the Form-Based Codes Institute (FBCI), “form-based codes address the relationship between building facades and the public realm, the form and mass of buildings in relation to one another, and the scale and types of streets and blocks. The regulations and standards in form-based codes are presented in both words and clearly drawn diagrams and other visuals. They are keyed to a regulating plan that designates the appropriate form and scale (and therefore, character) of development, rather than only distinctions in land-use types. This approach contrasts with conventional zoning's focus on the micromanagement and segregation of land uses, and the control of development intensity through abstract and uncoordinated parameters (e.g. FAR, dwellings per acre, setbacks, parking ratios, traffic LOS), to the neglect of an integrated built form.”8

The SmartCode in particular is a form-based, integrated land development ordinance into which zoning, urban design, public works standards and basic architectural controls are integrated into one comprehensive and streamlined document. As a unified ordinance, it effectively spans and coordinates all scales of development, from the region to the city, to the neighborhood and to the building. The SmartCode enables the implementation of the IGMC vision by coding the specific outcomes desired in particular places; to this end, it should be locally customized, or calibrated, to suit the local development context and conditions in Guiyang.

The SmartCode produces a

truly green, sustainable city with walkable and mixed-use neighborhoods,

transportation options, conservation of open lands, local character, housing

diversity and a vibrant downtown. Conversely, adopting the SmartCode for the

IGMC prevents it from becoming sprawl, from automobile dependency, from loss of

open lands, from single-themed Blocks and from unsafe streets and parks.

Being Transect-based, the

SmartCode ensures that the IGMC offers a full diversity of building types,

thoroughfare types and civic space types, and that they have characteristics

appropriate to their locations in the environment. With the SmartCode, it is

possible to coordinate best practices and standards across other disciplines

including transportation and environmental performance standards. The platform

of the Transect allows the integration of the design protocols of town

planning, traffic engineering, public works, architecture, landscape

architecture and ecology.

References

1. Madew, Romilly - Chief Executive, Green Building Council of Australia. Mr. Arab Hoballah, UNEP Chief of Sustainable Consumption and Production recently stated that the percent of the world’s water consumed by the building industry is now closer to 20%.

2. The Daily Galaxy recently reported on Chinese planners’ proposals to turn nine cities in the Pearl River Delta into a single megacity in the nation’s industrial heartland, stretching from Guangzhou to Shenzhen, with a population the of 42 million and “the size of Rhode Island, Connecticut and New Hampshire combined or 16,000 sq mile urban area that is 26 times larger geographically than metro London”, The Daily Galaxy, January 27 2011.

3. Duany Andres.“Asian Cities”, Newsweek–Specialeditionson"Asia's Urban Explosion", September-December 2003.

4. More information on Smart Growth and TNDs is available at smartgrowth.org and cnu.org.

5. By Smart Growth definition, a neighborhood comprises approximately 50 hectares, which is the area covered by a circle with a 400 m radius. Planning and sociology studies have shown that 400 m is the maximum distance a typical person will walk for his/her basic daily needs before getting into a car and driving. As such, for a community to be truly sustainable and walkable, it should be structured in neighborhood increments of this size, with basic daily needs provided within each neighborhood.

6. Crabtree Group, Inc. “Rainwater Strategy – Saratoga Springs, Utah”, 2011.

7. More information on Light Imprint urbanism may be found at lightimprint.org

8. Form-Based Codes Institute, formbasedcodes.org

9. Duany, op. cit.

Senen Antonio is a Partner with DPZ CoDESIGN (DPZ). Senen Antonio is an architect, urban designer and planner with nearly twenty years of international experience in sustainable design and planning, including plans for regions, military base redevelopment, transit-oriented development, disaster recovery, urban reclamation, revitalization and infill, and new towns, in Asia, Africa, Europe and North America.

Antonio has managed projects across all phases from conceptual design through construction. He lectures widely, with a recent focus on Asia, with government and university-sponsored lecturers in China, Laos, Indonesia, and the Philippines, and he contributes articles to professional journals.

Copyright © Global Forum on Human Settlements (GFHS)